From Feature Factories to Growth-Oriented Teams: A How-To Guide to Outcome-Driven Measurement

How to transform your product and data teams from just being feature builders to delivering measurable business value

If your company sets Objectives and Key Results (OKRs) like “Launch mobile app redesign by Q2” or “Implement five new dashboard features,” congratulations, you’re great at running a feature factory! With these output-oriented goals, you measure what you deliver, but not the impact it creates.

Now, consider outcome-focused goals instead, such as “Increase mobile user activation from 45% to 65%” or “Boost customer lifetime value by 20% through better recommendations.” These goals go far beyond. Instead of tracking tasks, they demonstrate the tangible impact your work has on the business and its users.

This is where data and metrics become essential for product-driven organizations. Without clear metrics, you make decisions based on opinions, gut feelings, or whoever has the loudest voice in the room. Data provides the objective foundation to validate whether your products are actually working, which features drive value, and where to invest next. More importantly, metrics create accountability: they force teams to define success upfront and honestly assess whether they achieved it.

Shifting from outputs to metric-driven outcomes is worth it, but it’s not always easy. In this article, I walk you through the most common challenges organizations face and share practical strategies to overcome them.

I begin with the basics: the difference between output and outcome, plus a quick exercise to help you spot it in action.

What is the difference between outputs and outcomes?

One of the most common mistakes organizations make when starting goal setting with OKRs is confusing outputs with outcomes. The distinction is important to understand, so let’s see if it becomes clearer with the by-the-book definitions and some examples:

Outputs are what you produce. Features shipped, reports generated, experiments launched. They’re tangible, controllable, and comfortable to measure.

Outcomes are what you achieve. Customer behavior changes, business metrics improvements, and user experience enhancements that result from your outputs.

Now, can you guess which of the following goals are outputs vs which ones are outcomes?

Increase mobile user activation rate from 45% to 65%

Launch redesigned checkout flow by the end of Q2

Improve customer lifetime value by 20% through better recommendations

Reduce customer churn rate from 8% to 5% within 6 months

Run 3 A/B tests this quarter

Complete migration of the legacy dashboard to the new platform

You guessed it right if you think objectives 1, 3, and 4 are outcome-based. And while it might be easy to do such an exercise, I recall that I didn’t have it that clear the first time I participated in implementing OKRs more than 10 years ago.

We required numerous iterations, coaching, and asking the right questions to achieve more outcome-based OKRs that would guide our work. Additionally, I recall us improving quarter by quarter by simply reflecting on it and trying to improve, having more metrics to choose from, and calculating KR baselines just in time to set goals. So, don’t worry if you feel a bit stuck right now.

Iteration is essential, and so is simplicity. What follows is my first recommendation for implementing company-wide OKR systems.

How many OKRs should you have?

OKRs were created by Andy Grove at Intel in the 1970s, building on Peter Drucker’s Management by Objectives (MBO) framework. Later, in 1999, John Doerr implemented OKRs at Google, and their popularity expanded. Doerr published what might be the most influential book on OKRs in 2018, Measure What Matters, in which he quotes Andy Grove for the number of Objectives an organization might have:

“The one thing an [OKR] system should provide par excellence is focus. This can only happen if we keep the number of objectives small… Each time you make a commitment, you forfeit your chance to commit to something else. [...] We must realize—and act on the realization—that if we try to focus on everything, we focus on nothing”.

“The art of management lies in the capacity to select from the many activities of seemingly comparable significance the one or two or three that provide leverage well beyond the others and concentrate on them.”

On the number of Key Results, Doerr mentions: “If an objective is well framed, three to five KRs will usually be adequate to reach it”.

So in summary, a few objectives with a few KRs. And then, the community organically adopted the 3x3 framework (three objectives with three key results each) because of its simplicity and elegance.

In such a system, with nine total key results to track, companies can maintain clarity and accountability while still having enough metrics to capture different dimensions of success.

That said, the 3x3 rule is a guideline rather than a hard rule. Some companies may require 2-5 objectives or 2-4 key results, depending on their specific context.

With the company’s OKRs set at approximately 3x3, the next step is to explain the most common dysfunction in organizations adopting OKRs.

The Cascading OKR Trap (And How to Escape It)

Many small and medium-sized organizations (with up to 500 employees) make the mistake of excessive cascading when setting OKRs. They create 3x3 outcome-oriented company-level OKRs, which is good. And then, each department or function creates its own OKRs, and then each team makes its own OKRs.

This creates a complex and unnecessary hierarchy of goals that dilutes focus and encourages siloed thinking.

Picture this scenario: The company sets a KR to “Increase annual recurring revenue (ARR) by 30%.” Then, the Product team creates its own KR: “Launch three major features to drive revenue growth.” The Data team responds with: “Provide analytics support for product feature launches.”

On the surface, this seems logical, but in reality, you’ve created a game of organizational telephone where the original outcome gets lost in translation due to the company’s organizational structure.

The alternative approach is simple: minimize cascading.

Starting with clear company-level outcomes-driven OKRs is great. You can set yearly company OKRs and then break them down into quarterly goals.

But after that, every team should contribute directly to those outcomes rather than creating intermediate goals. If the company wants to increase ARR by 30%, cross-functional units should identify specific initiatives that directly impact that metric.

A cross-functional User Activation team, comprising a Product Manager, a UX Designer, data professionals, and engineers, might focus on improving user activation rates within the first 30 days and measure its contribution to ARR. They don’t need a specific OKR for that.

If there are any activities that they do that are not part of the company’s OKRs, that’s fine too. Just have them written somewhere as other deliverables or operational activities.

When Cascading OKRs Actually Works

I recommend minimal cascading in most situations, but I agree that it may be the only viable option in certain contexts. Cascading makes sense when you have a large organization (think 500+ employees) or when you have distinct business units that operate semi-independently. In these cases, one additional layer of cascading can provide clarity without creating bureaucracy.

For example, if your company has separate divisions serving different markets or customer segments, each division may need its own OKRs that align with company objectives. The key is to limit cascading to one additional layer and ensure that each level maintains a focus on outcomes.

Now, creating and maintaining cross-functional teams can also be challenging, so I outline what typically works in the next section.

How to create cross-functional autonomous product teams

Suppose you work in an organization where a Business Manager is ultimately responsible for deciding what to do and when, and he/she spends the day talking to Engineering, Data, and User Experience to get his/her needs and goals fulfilled. In that case, you are in the opposite spectrum of what a cross-functional autonomous product team should be.

In cross-functional product teams, no single function is treated as a support function, merely answering questions, creating mock-ups, or reports for others to interpret. Cross-functional product teams have the necessary members from each function (engineering, data, product, and user experience) to focus on solving a specific user or business need or opportunity.

What is more important, they have the autonomy to suggest and validate what to work on. For example, suppose the company’s goal is to increase profitability, and the team scope is user recommendations. In that case, the team should have the capacity to ideate, validate, and measure which initiative makes sense to prioritize at this time.

In such cases, there is no need for OKRs to cascade into functions using different wording. What might make more sense is to identify the possible contribution of the team to a given OKR.

While minimizing cascading prevents the organizational telephone problem, you still need a structured way to connect company OKRs to team initiatives; that’s where the W Framework comes in.

The W Framework

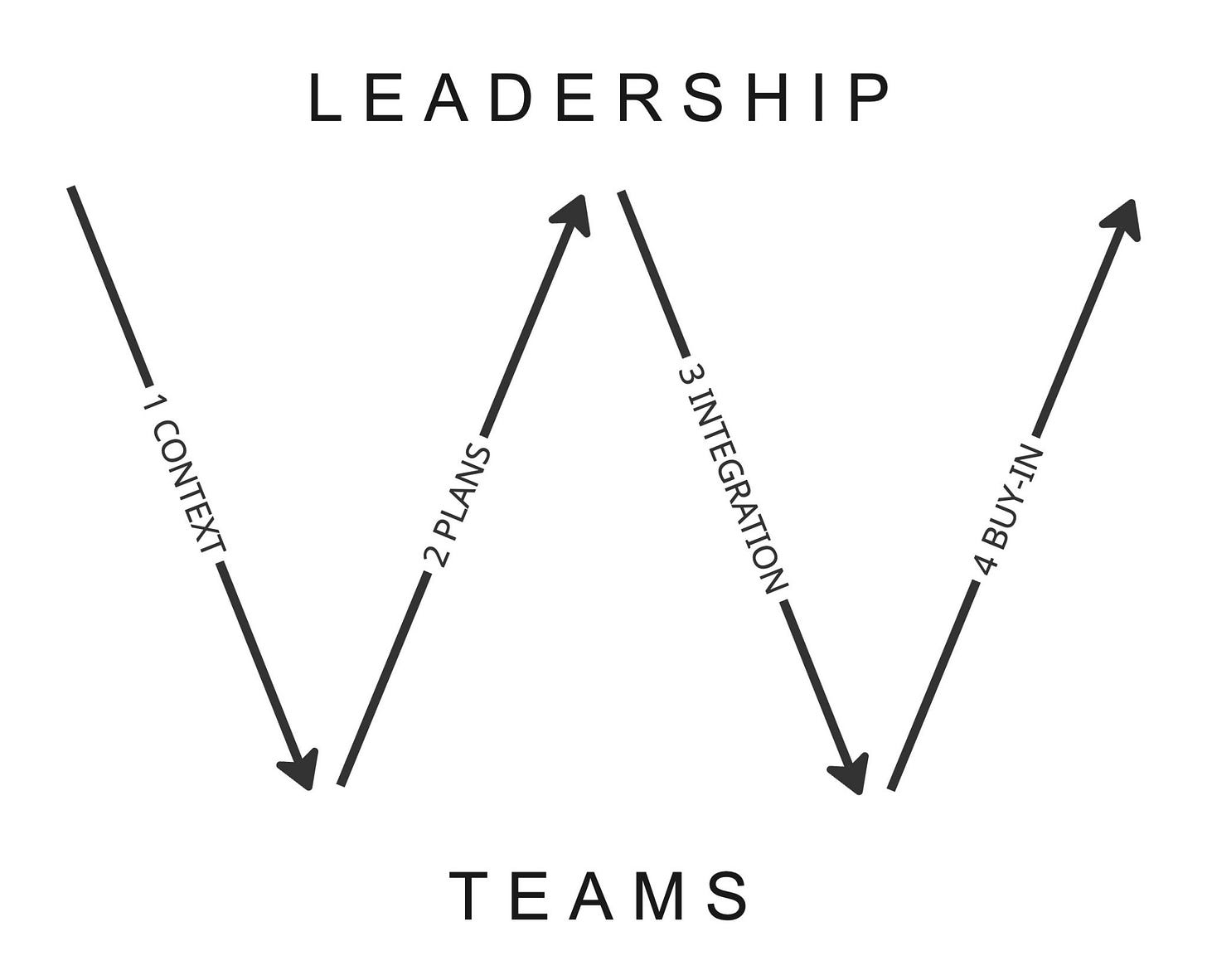

When cross-functional teams receive company direction in the form of company OKRs, they need a structured process to propose how they’ll contribute. The W Framework, developed by Lenny Rachitsky and Nels Gilbreth and illustrated next, provides exactly that structure.

The framework creates a four-step conversation between leadership and teams. First, leadership shares context: the high-level strategy and company OKRs. Second, teams respond with proposed plans and initiatives they believe will improve those OKRs. Third, leadership provides feedback and integrates all team plans into a cohesive approach. Fourth, teams make final adjustments, confirm their buy-in, and start working.

This back-and-forth ensures alignment without the rigidity of cascaded OKRs. Teams maintain autonomy in proposing solutions while leadership ensures coherence across the organization.

Most companies run this exercise each time executives share their chosen strategy. Some do it quarterly, others biannually or annually, depending on their planning rhythm and organizational maturity.

Now, you might be thinking: “This all sounds great, but where do I actually begin?” The answer depends on your role within the organization and the timeline you’re working with.

Where to start when implementing OKRs

Your starting point depends on two factors: your role and your planning horizon. I break this down into two scenarios: what to do in the next quarter versus planning for the next year, and how your responsibilities differ whether you’re a team manager or part of senior leadership.

For Senior Leadership: Setting the Foundation

If you’re a CTO, CDO, CPO, or VP of a small to medium organization (500 employees), your first move is to resist a common temptation: don’t request OKRs from every department and team. This creates the cascading trap I described earlier.

Instead, focus your energy on two critical activities:

First, establish clear company-level OKRs. Involve your leadership team in identifying 2-4 objectives, each with 2-4 key results. Start with outcome-based goals whenever possible, but avoid getting stuck in analysis paralysis, seeking perfection. If some of your key results are output-based in your first iteration, that’s fine. As mentioned earlier, companies significantly improve their OKR quality simply by running the exercise quarter after quarter.

Second, ensure that teams connect their initiatives to the company’s OKRs. Rather than demanding team-level OKRs, implement the W Framework. Make it clear that every prioritized initiative should map to at least one company objective. If teams are working on something that doesn’t connect to any company OKR, that’s a signal to investigate whether the work is truly strategic.

For Team Managers: Moving Toward Outcomes

If you’re leading a product team, data team, or engineering team, your approach differs based on your planning cycle.

For quarterly planning:

Start by auditing your current goals. Take some time and categorize each goal as output-based or outcome-based. If most of your goals are outputs (features shipped, reports delivered, systems migrated), you now have clarity on what to change.

For your next planning cycle, try converting just one or two output goals into outcome goals. Instead of “Launch new recommendation engine,” ask yourself: “What user behavior or business metric should this recommendation engine improve?” That becomes your outcome: “Increase average session duration from 8 minutes to 12 minutes through better content recommendations.”

If you don’t have baseline metrics for your proposed key results, don’t wait. Calculate them now using available data. If the data doesn’t exist, identify proxy metrics you can measure today.

For annual planning:

Use the longer horizon to build your measurement foundation. Identify gaps where you lack measurement, then prioritize closing those gaps based on business impact by considering which metrics you can influence and how they are related.

Document clear definitions for each metric you track. Get stakeholders to agree on these definitions. I’ve seen too many debates about whether metrics are improving simply because different teams calculated the same metric differently.

Now, in the next section I present other “smaller” challenges on the process and ways to overcome them.

Challenges and How to Overcome Them

Implementing outcome-oriented measurement sounds easy in theory, but you’ll face resistance and obstacles from various parts of your organization. I’ve encountered these challenges repeatedly across different companies, and I present the most common ones as follows, along with practical strategies to address them.

Missing Metric Baselines

Teams often attempt to set metric targets without established baselines, creating goals that remain in perpetual limbo, such as “Increase active users from X% to Y% (baseline pending).”

Solution: Start with imperfect data. Use proxy metrics when direct measurement isn’t feasible. Run focused “data sprints” to define, instrument, and establish initial measurements for critical metrics.

Teams Don’t Act on OKRs

Teams struggle to translate high-level metrics into actionable daily activities, resulting in “set-and-forget” company objectives with little impact on actual work.

Solution: Increase OKR visibility through weekly check-ins and dashboards. Implement OKR syncs where teams report their current metric status, discuss initiatives that impact metrics, and identify blockers.

Orphaned Metrics

Key metrics remain unchanged when they lack clear ownership, with each team assuming someone else is responsible for improving them.

Solution: Explicitly assign ownership of each key result to a specific team leader. For cross-functional metrics, designate one metric “owner” accountable for coordination.

Technical Debt Prioritization

Outcome-driven approaches can inadvertently marginalize critical non-business initiatives, such as addressing technical debt, that don’t directly impact customer-facing metrics.

Solution: Allocate dedicated capacity (typically 20-30%) to engineering-led initiatives on a quarterly basis. Frame large technical initiatives in terms of business outcomes when possible.

Metric Overload

Organizations track dozens or even hundreds of metrics, creating analysis paralysis as teams try to improve everything simultaneously.

Solution: Limit each team to focusing on 1-3 company key results and metrics during any given period.

And with this list of challenges, you’ve made it to the end of the chapter. The last section summarizes the article and its key takeaways.

Summary and Key Takeaways

Shifting from output-oriented to outcome-oriented measurement represents one of the most important transformations an organization can make. The transition requires patience and iteration. Your first (and second) list of OKRs won’t be perfect. You’ll have missing baselines, some output-based goals, and teams struggling to connect daily work to quarterly metrics. That’s normal. Every organization I’ve worked with improved quarter by quarter simply by running the exercise, reflecting on what worked, and trying again.

Here are the key takeaways:

Outputs are what you produce; outcomes are what you achieve. Features shipped don’t matter if user behavior doesn’t change or business metrics don’t improve.

Keep OKRs simple. Follow the 3x3 framework to start with: three objectives with three key results each. More than that creates complexity without adding clarity.

Minimize cascading. Have teams contribute directly to company OKRs rather than creating cascaded departmental goals that play organizational telephone with your strategy.

Use the W Framework for alignment. Let leadership set the context and company OKRs; teams propose plans, leadership integrates feedback, and teams confirm buy-in before execution.

I hope this article has been helpful. Please let me know if you have any further challenges or ideas on implementing OKRs in organizations!

Enjoyed this post? You might like my book, Data as a Product Driver 🚚.

Love your points here on minimizing cascading OKRs and getting everyone rowing in the same direction. Especially great advice on starting with imperfect data!